chocolate milk cow milk

Hae Won Sohn

Feb 7 - March 25, 2023

Unaccustomed Earth could have been the title of Hae Won Sohn's solo show, the first one in her native country. (It is the title of the book I translated years ago, which Jhumpa Lahiri, an Indian-American writer, wrote.) Since Nathaniel Hawthorne uttered his famous prophecy in 1850, "Human nature will not flourish, any more than a potato, if it be planted and replanted… in the same worn-out soil. My children have had other birthplaces and… shall strike their roots into unaccustomed earth." human nature indeed flourished. Hae Won Sohn was born in Korea in 1992, and moved to Davis, CA, when she was four years old, where her father was doing his Ph.D. at UC Davis. After four years, in 2000, her family moved back to Korea, where Sohn spent most of her adolescent years. Sohn studied ceramic crafts at Kookmin University in Korea before she pursued her graduate studies at the Cranbrook Academy of Arts, MI, in 2016. Since finishing her program in a small city outside Detroit, she has had more than five studios in Long Island City, NY, Baltimore, MD, and Brooklyn, NY, constantly going back and forth between places. Now she feels more settled in NY, living in Queens and working in Brooklyn. Undoubtedly, Sohn is one of many children of Hawthorne.

To anyone who experienced a relocation that required moving from one culture to another, they would feel the impact of the phrase "shall strike their roots into unaccustomed earth," the physical hardness of the "earth" and the sheer amount of force it takes to "strike their roots." Considering her peripatetic life, it is all the more poignant to think about aspects of Sohn's practice. She studied ceramics in the field of "Crafts," not in the fine arts, if there is any distinction, dealing with clay, with all the physical labor and technicality that goes into it. While she was studying and learning, her mind was already bridging fields of practice and merging different histories of skill sets. The program at Kookmin University focused on the traditional approach to ceramic making in Korea. Interestingly enough, with her mind already taking off from the traditional approach, she transplanted her roots to American soil and enrolled in the ceramics department at Cranbrook, where the tradition of making ceramics is also practiced and celebrated. In this program, she decided to explore an industrial technique called "slip-casting," used to make porcelain amenities like toilets. While in the industry, they would repeat the process to produce the same model in large numbers; she utilized this method to create "unique multiples."

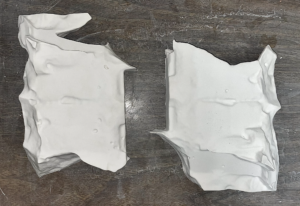

In traditional sculpture practice, sculptors make multiples as well. They build a form and mold to produce the same work repeatedly. Here, their goal is to get the form. Watching how the process of making multiples go, Sohn decides to try it differently. Her "standard" process can be like this; she would make an object, make the mold, then break the mold, attach the broken piece of mold to an object, make a new mold from that combined object, and repeat the process. For her, making mold is not to contain the form; it is to break out of a form. Sohn says that her sculptures "develop their structural genesis based on a repetitive process of making molds, breaking molds, casting molds, breaking the molds of molds, casting the molds of molds, and so on. The concept of casting and mold-making become homogeneous as the mold becomes the cast and vice versa. Fragments of the cast form migrate to the mold, making the positive and negative dichotomy indistinguishable.”

Auguste Rodin is a sculptor who paid unprecedented attention to using fragments of sculpture. While working on a massive project The Gates of Hell, he amassed many complete figures and their fragments. Even before this project, he experimented with partial figures and body parts as he did with The Torso of Walking Man and showed only the body parts of a figure he called abattis. Rodin dismantled and reassembled the pieces from different origins in an unexpected way. The well-known examples are Female Torso with the Hand of a Skeleton on her Belly (c 1890), The Mask of Camille Claudel with the hand of Pierre de Wissant (c 1895), and Torso of the Woman Centaur and Minotaur (c. 1910) among many. Upon writing Rodin's monograph, Rainer Maria Rilke observed that "Never was human body assembled to such an extent about its inner self, so bent by its own soul…." Parts of the human body naturally evoke a sense of an "inner" state; it reveals the abstract aspect of the human form and existence and makes us think about the making of it.

A sculpture is something we see; we don't get to see the process of making one. Sohn went directly into the realm of the invisible, taking the entire process of making sculpture as her subject matter and manipulating it as if it were clay. The resulting form itself is less of an issue for her. It is more important how she deals with the dichotomy between visible and invisible, inside and outside, negative and positive, intended and accidental, and so on. Her "space" as an artist is in-between. Even though she majored in ceramic crafts in Korea, her work barely shows her background. But the business of dealing with the unexpected, the accidental—often disastrous— aspect of making Korean ceramics, is embedded in her work. She takes that aspect of the process and turns it into something productive.

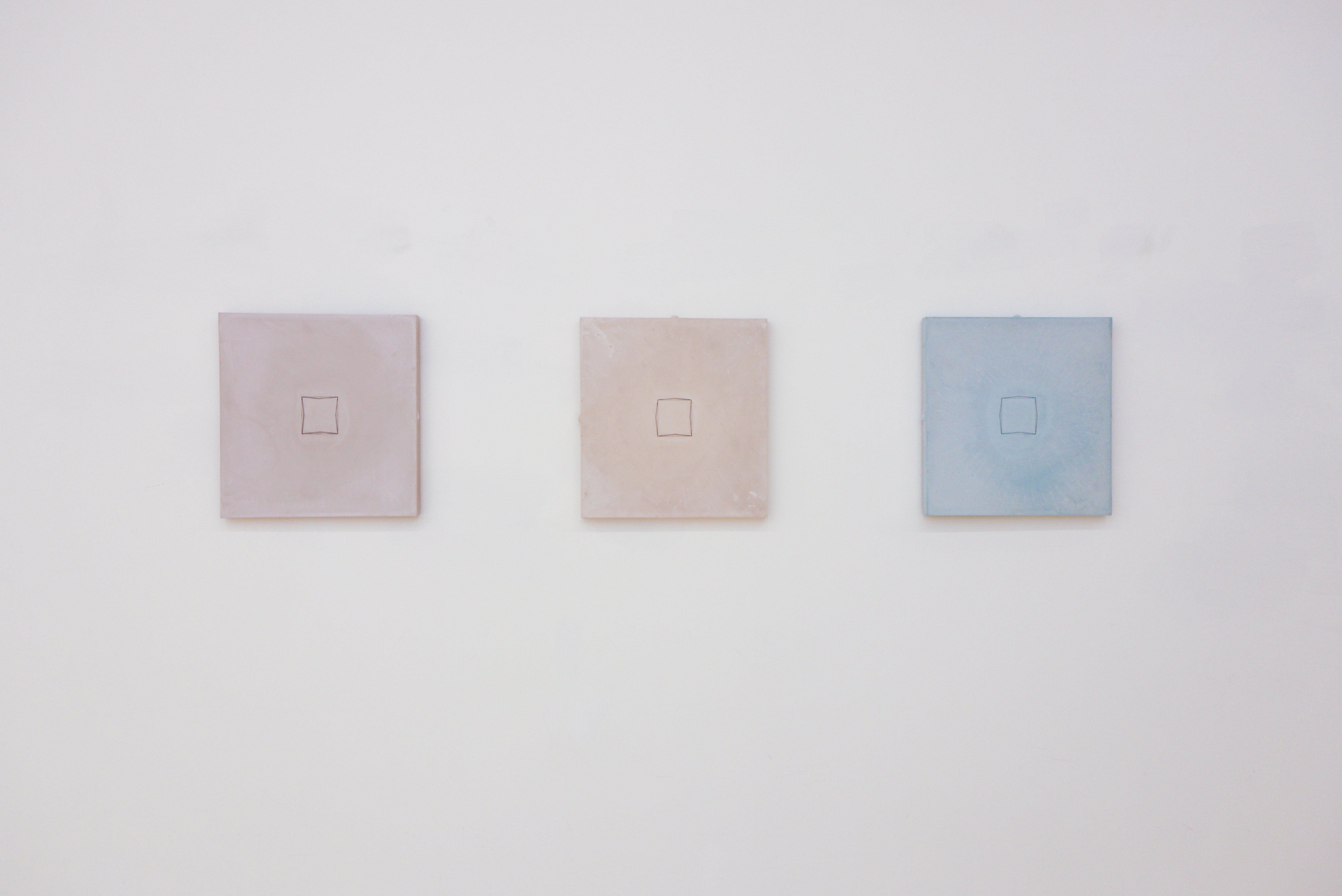

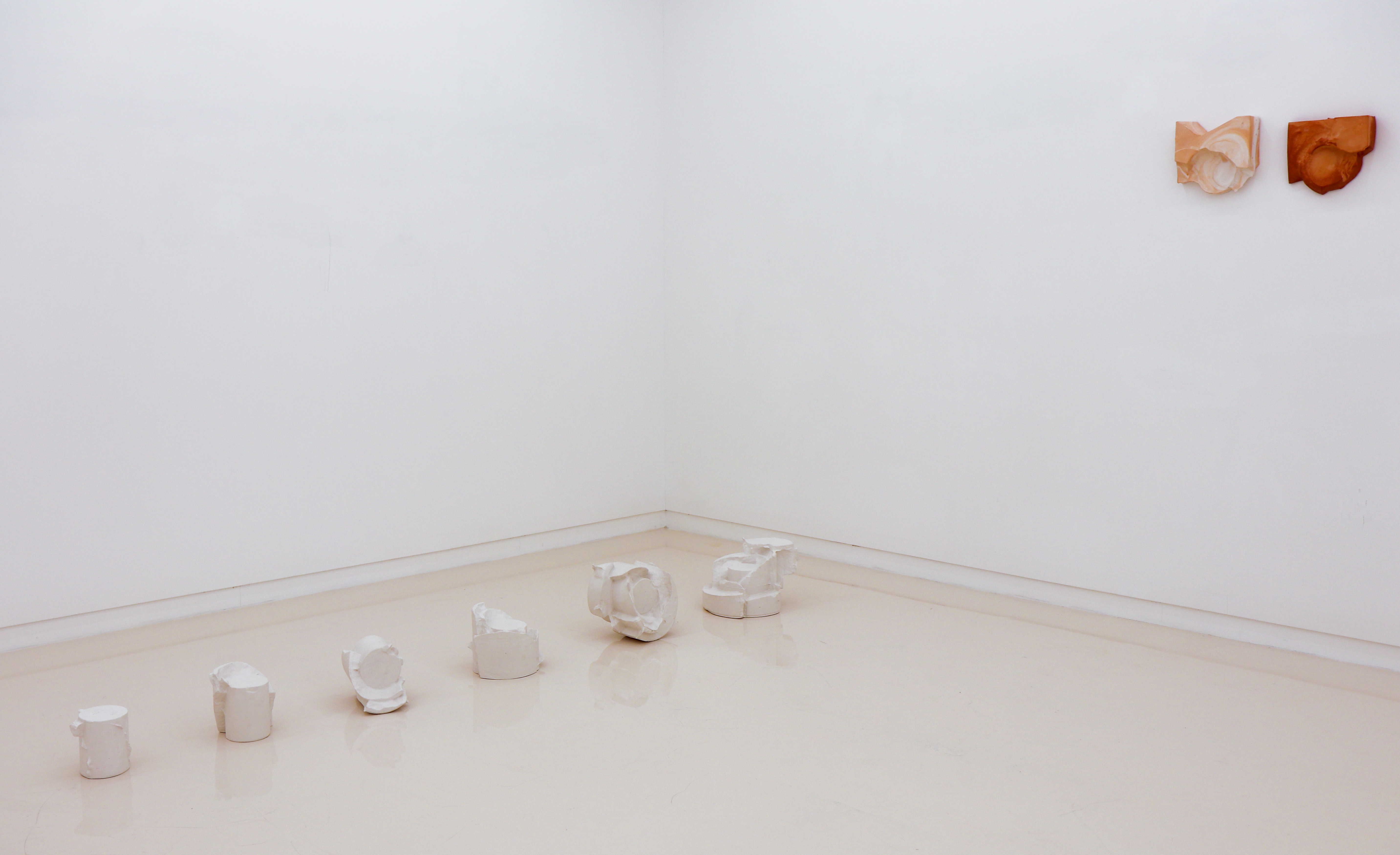

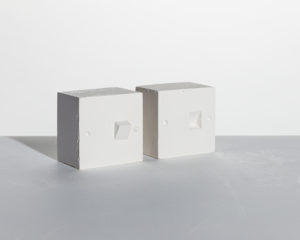

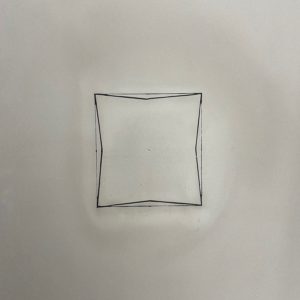

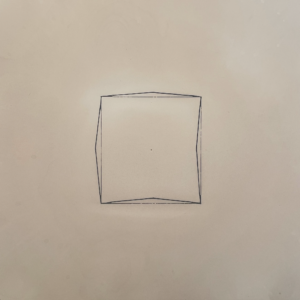

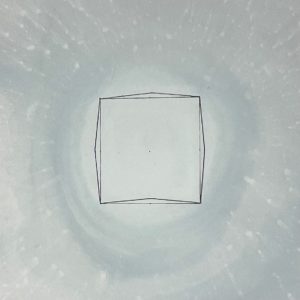

She would make a form like a cylinder for an original form to cast. I think of Cezanne when I think of a cylinder; however, Sohn's concept of a cylinder comes from a factory's production line, for a cylinder is one of the most often used forms of mold in factories. Square Dreams (2020) is a "procession" of six pieces that are "borne" of and break out of a cylinder. It is a procession of six "stages" of a cylinder transforming into more complex forms with the addition of fragments of mold. It is funny she titled it Square Dreams because there is no square in sight. Is a cylinder a square's dream? Sohn advises that Square Dreams is a work that evolved from her previous work, Hiatus(2018), which was a procession of a cube progressing to complex forms. Self-referencing, repeating forms she already made, is part of her methodology of creating “unique multiples.”

In chocolate milk cow milk (2022), it is vague if it is a progression or a repetition. Four arc-like forms are attached to the wall varying in size and color. All objects look like broken pieces; one on the far right seems broken in half. These are fragments of molds of the mold of (chrysanthemum) (2022), which came out of the mold of Square Dreams. In (chrysanthemum), the arc-like objects look like parenthesis, whereas in chocolate milk, they look like the bows or ribs of cows. She gives the work titles loosely inspired by associations, wordplay, and innate metaphors and there is always enough space given between the work and the title. In chocolate milk cow milk, each object may correspond with each word in the title, she suggests. Or the whole thing might be an allegory of how the artificial (e.g., art) intertwines with nature(e.g., material), the form with language.

I am not sure if Hae Won Sohn will ever “strike her root” into unaccustomed earth. But she lives on and with "unaccustomed earth," exploring unknown territory like a child playing in a new playground. She seems to do everything with such ease, playfulness, and yet everything works on a metaphorical level. In Lion Heart(2022), a cube's corner protrudes through what looks like rubbles. Does it look like a civilization peeking through rocks? It might even appear when her work reveals its form in the material and process. With all its metaphorical power, it does have a shape of a heart. Yes, it may take a heart of a lion to roam about unaccustomed earth.

Mimi Park

손해원의 개인전, 모국에서 열리는 그녀의 첫 전시

한 문화에서 다른 문화의 이주를 경험한 사람이라면 "

전통적인 조각 분야에서도 조각가들은 에디션을 만든다.

오귀스트 로댕은 조각의 파편을 다시 이용하는데

조각은 눈에 보이지만 이를 만드는 과정은 눈에 보이지

예를 들어 그녀는 원기둥으로 원형을 만들고 캐스팅한다.

<초코 우유 젖소 우유>(2022)에선 작품들이 어떤

손해원이 길들지 않은 땅에 결국 “뿌리를 내릴”

박상미